Primer 1: Foundational Concepts of Diagnostic Error

Summary

This is Part 1 of a three-part series of primers dedicated to diagnostic error and excellence. Primer 1 focuses on the foundations of diagnostic errors, including types errors and impact on patient safety. Primer 2 explores system approaches to diagnostic excellence. Primer 3 examines clinician approaches to diagnostic excellence.

Background

The 2000 Institute of Medicine report “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System”1 focused national attention on the role of the diagnostic error in patient safety. Prior to the report, efforts to improve patient safety were concentrated on medication errors, healthcare-associated infections, and postsurgical complications, and work to reduce these important causes of morbidity and mortality continues. New research has been focused on identifying the impact of diagnostic error, conditions and diagnoses that are vulnerable to diagnostic error, and prevention strategies. Diagnostic error is now considered a leading source of preventable harm in U.S. healthcare systems in current times.2

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine defines diagnostic error as “the failure to (a) establish an accurate and timely explanation of the patient’s health problem(s) or (b) communicate that explanation to the patient”. Alternatively, the World Health Organization defines diagnostic error as being “completely missed, wrong, or delayed”.3 Examples of diagnostic errors include an incomplete history or exam, the misinterpretation of physical, laboratory or radiologic findings, or a lapse in communicating important findings to the patient. Both definitions emphasize the critical role of timing in diagnosis as patient harm can result from delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Unfortunately, diagnostic errors are all too common. Across care settings, a 2024 cross-sectional study estimated 2.59 million missed diagnoses which resulted in 795,000 serious harms.2 While only a fraction of diagnostic errors results in harm, given the millions of diagnoses made every week, the aggregate amount of harm is substantial. Every diagnostic error, regardless of harm or cost, presents an opportunity to study and improve the diagnostic process, with the goal of preventing harm in the future.

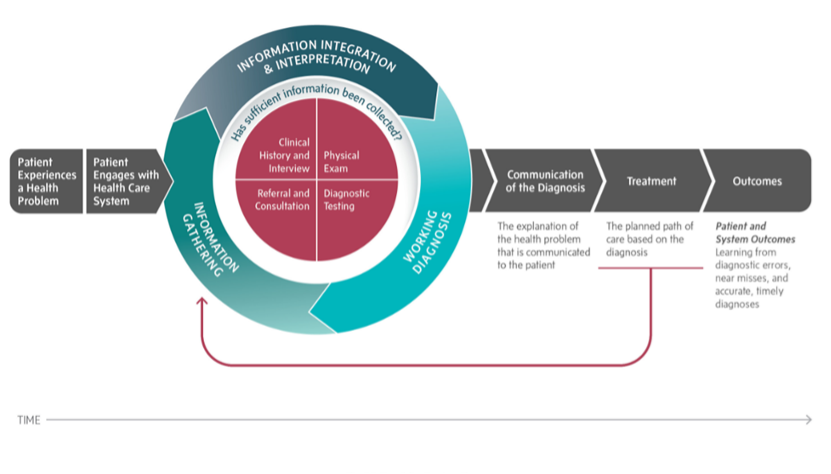

Figure 1. The Diagnostic Process

Source: Reproduced with permission from the National Academies Press.4

The formal diagnostic process (Figure 1) begins when the patient experiences a health problem or a health problem is identified by the healthcare system.4 It is increasingly common for patients and family to first investigate health concerns utilizing the internet and/or community connections or use point of care testing prior to formal engagement with the traditional health system. After the clinician evaluation, the patient enters a cycle of information gathering, information integration, and interpretation, resulting in a working diagnosis, or establishing the most likely set of possibilities: the differential diagnosis. Communicating the diagnostic possibilities and uncertainties to the patient is a critical step of the process. The information created by diagnostic testing and/or referral and consultation are used to produce a diagnosis and a treatment or management plan. Ideally, diagnosis is an iterative and collaborative process that involves the patient, clinicians, subspecialists, and diagnostic testing services as appropriate. Patients may re-enter the information gathering stage as symptoms change or evolve, or in response to new findings. The diagnostic process can be complicated and involve multiple healthcare encounters occurring over days, weeks, or even months. Initial diagnostic possibilities may be refined, changed, or ruled out as this process evolves, and this process of refinement is valuable and natural, and outcomes of refinement are not always a diagnostic error.

Popular television shows and movies have sensationalized the diagnosis of rare or unusual conditions; however, the data exploring misdiagnosis reveals a different story. A 2019 cross-sectional analysis of large medical malpractice claims identified most diagnostic errors occur in three common categories: vascular events (such as stroke or myocardial infarction), infections, and cancers.5 Noteworthy, this study found these “Big Three” broad categories account for about three-fourths of serious misdiagnosis harms.5

While a diagnosis can be missed by under testing and missed diagnosis, patient harm can also come/arise from over testing and over diagnosis. For example, a patient may have a reaction to contrast dye used in a computed tomography scan (CT scan) or be prescribed an unnecessary medication. Diagnostic stewardship refers to “strategies to guide the optimal use and interpretation of tests, improving processes, and systems to support clinical decision-making, and tracking and learning from patient safety events related to missed, delayed, or incorrect diagnoses” and is a core element of diagnostic excellence.6 It can also be thought of as ordering “the right test, for the right patient, to prompt the right action”.7

Central to the diagnostic process is the patient. Patient engagement is essential in the diagnostic process, starting with communicating the history and their symptoms, understanding the risks and benefits associated with testing, appreciating any residual uncertainty, and in the creation of a treatment plan. Additionally, patients and families have an important role to play in advocating for health policy and research supporting diagnostic excellence.8

Types of Diagnostic Errors

How Errors are Recognized

Errors have been identified by autopsy, patient experience surveys, provider surveys, morbidity and mortality conferences, chart reviews, malpractice claims, and analytical methods that measure discrepancies in documentation (for example, initial and discharge diagnosis). While this diverse methodology contributes to a rich understanding of error types, the heterogeneity in methods can make comparisons and validation across research studies challenging.

Taxonomy of Diagnostic Errors

Diagnostic error taxonomy, like error recognition, reveals varied approaches to the classification of diagnostic errors. For example, errors can be categorized by a specific diagnosis or diagnostic categories, level of healthcare system involvement, impact to the patient, care setting (inpatient versus outpatient), age (pediatric or geriatric), and economic cost.

Regardless of how the information is collected, the research shows diagnostic error has an impact across a variety of diagnosis, care settings, and diagnostic processes and results in significant patient harm and economic cost.

|

Error Classification |

Study Example |

|

Diagnosis or Diagnosis Category |

A 2019 cross-sectional analysis of large medical practice claims identified most diagnostic errors occur in three common categories: vascular events (such as stroke or myocardial infarction), infections, and cancers.5 A 2009 survey of physician self-reported diagnostic errors found pulmonary embolism was the most common missed diagnosis. Cancer was the largest reported disease category.9 |

|

Diagnostic Process

|

A 2021 qualitative study of clinician focus groups found clinicians perceive diverse organizational, communication, coordination, individual clinician, and patient factors can interfere in the process of diagnosis.10 A 2009 survey of physician self-reported diagnostic errors found failure or delay in considering the correct diagnosis accounted for the largest amount of diagnostic failures.9 A 2005 examination of 100 causes of diagnostic error in internal medicine found that systems-related factors were involved in 65% of cases and cognitive factors in 74% of cases.11 |

|

Significance of Harm |

A 2024 cross-sectional study estimated 2.59 million missed diagnoses which resulted in 795,000 serious harms.2 A 2009 survey of physician self-reported diagnostic errors found that 28% of errors were reported to be major in severity, 41% moderate, and 22% of minor impact.9 |

|

Errors by Setting (Inpatient versus Outpatient)

|

A 2017 study found of malpractice claims related to diagnosis, 61.2% of claims occurred in the outpatient setting, and the remaining 38.8% occurred in the inpatient setting.12 Inpatient A retrospective chart review from 2023 found among patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19, diagnostic errors were identified in 14% of cases.13 A meta-analysis from 2020 found that 0.7% of adult admissions involve a harmful diagnostic error. 14 A 2017 hospital autopsy study found critical findings such as untreated infection, pulmonary embolism, and undiagnosed malignancy were unrecognized in 9.9% of autopsies.15 Outpatient A 2021 longitudinal patient record review found breakdowns in the patient-practitioner encounter such as history-taking, examination, or ordering tests in 68% of cases. The interpretation of diagnostic tests was involved in 35% of errors, and 48% involved follow up and tracking of diagnostic information; 37% of errors resulted in moderate to severe avoidable harm.16 A 2014 large outpatient observational study identified the rate of outpatient diagnostic errors of 5.08%, affecting approximately 12 million adults each year. Authors estimate that approximately half of these errors could cause harm.17 A 2013 study of primary care diagnostic errors found that process breakdowns were common involving patient-practitioner clinical encounters. Of these, 56.3% involved history-taking, 47.4% involved examination, and 57.4% involved ordering tests for further workup. Most errors had the potential to cause moderate to severe harm.18 |

|

Age |

A 2014 retrospective chart review identified 5% of children admitted to the hospital had a diagnostic error.19 A 2016 systematic review of misdiagnosis found under and over diagnosis were common in older patients.21 |

|

Economic Cost |

A 2012 chart review study found errors resulted in predicted costs of $174,00 across 399 visits. Authors note chart review alone underestimates cost of care.20 |

Current Context

Managing Patient Safety and Diagnostic Error

First generation safety science focused on preventing errors in what is known as “Safety I.”22 Reactive tools like root cause analysis center on understanding poor outcomes after the fact and designing appropriate interventions.23 Safety I initially developed in high-risk industries outside of healthcare, namely aviation and nuclear power, and has realized remarkable success in improving safety in these industries. Much of this progress derives from exceptionally well-developed systems to capture and study safety risks. The Aviation Safety Reporting System, for example, receives and analyzes over 8,000 safety concerns each month.24 Building on successes from these industries, organizations like the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) have advocated for legislation to create and protect healthcare error disclosure and analysis, including standardized formats for event reporting. However, error reporting in healthcare still relies on busy providers taking time to report concerns in reporting systems that vary from hospital to hospital, clinic to clinic. Healthcare organizations today, even those at the leading edge, have rudimentary error-reporting systems by comparison, and a major hurdle is that providers typically don’t take the time to report the many concerns they encounter. A second major issue is that aviation and nuclear power rely on highly standardized procedures and equipment that can be adjusted precisely; healthcare, in contrast, is dynamic and complex, and relies on the dedication, resilience, and creativity of staff to ensure safety.

Another approach, “Safety II”, focuses on the study of what goes right, not system breakdowns.25 This approach is the inverse of Safety I; it is proactive rather than reactive and focuses on designing processes that enable processes to succeed as often as possible. The goal of Safety II is to create organizations that are resilient, flexible, and adaptable by studying how high-performing organizations are successful, instead of how they fail.

The latest organizational approach is referred to as “Safety III” or systems safety. Instead of focusing on piecemeal processes and how things can go wrong (Safety I) or right (Safety II), Safety III focuses on designing an entire system to reduce hazards that can cause errors. Safety III acknowledges that it can be difficult to adhere to strict protocols to prevent errors, or for humans to always be successfully resilient to challenges.26 Instead, Safety III uses human-centered design tools to create a system that works for the “users", whether they are patients, providers, or staff. The SEIPS 101 framework provides approaches to design systems, processes, and outcomes with the user experience in mind.27

Tackling Diagnostic Error

Systems-Based Approaches to Diagnostic Error

Systems-based approaches focus on monitoring and measurement of the types and causes of diagnostic error and systems-based interventions, such as enhancing communication and teamwork. The primer “Systems-Based Approaches to Diagnostic Excellence” has a full discussion of background, measurement frameworks, and interventions.

Clinician Approaches to Diagnostic Error

Clinician approaches to avoiding diagnostic error focus on strengthening diagnostic reasoning and identifying and addressing cognitive bias. The primer “The Role of Clinical Reasoning in Diagnostic Excellence” contains a detailed discourse on the diagnostic process, types of bias, and interventions.

Patients and Patient Advocates

Patients and advocates play an important role in preventing diagnostic error. Unfortunately, patients and advocates may encounter barriers to participation, such as fear of being seen as difficult, feeling powerless, uncertain about the health system, or how to resolve a dispute when there is a difference of opinion with healthcare professionals.8

There are several strategies patients and patient advocates can use to reduce the likelihood of a diagnostic error and improve healthcare quality and safety.

- Use a patient toolkit for diagnosis. The toolkit helps patients and patient advocates “tell the story of medical concerns and discuss goals of care.28

- Review notes and documentation in the electronic health record (EHR). Take notes and share any concerns or inaccurate information with your healthcare provider.28

- If you are concerned that a diagnostic error has occurred, you may choose to discuss the concerns with your healthcare provider, report it to the institution, or seek a second opinion.8

- Consider participating in a Patient and Family Advisory Council (PFAC) to provide feedback and advice.30

- Participate in shared decision-making, which is a way for patients and care teams to work together to make decisions.28

- Advocate for health policy and research supporting diagnostic excellence.8

___

Authors

Roslyn Seitz, MSN, MPH

Associate Editor, AHRQ’s Patient Safety Network (PSNet)

Health Sciences Assistant Clinical Professor

University of California, Davis

[email protected]

Diana M. Funk, MD, MBA

Chief Resident, Internal Medicine

University of California, San Francisco

[email protected]

Maritza T. Harper, MD, MS, FAAP, FACP

Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics

University of Pittsburgh

[email protected]

Mark L Graber, MD, FACP

Founder, Community Improving Diagnosis in Medicine (CIDM)

Professor Emeritus, Stony Brook University, NY

[email protected]

This primer was funded under contract number 75Q80119C00004 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors are solely responsible for this report’s contents, findings, and conclusions, which do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Readers should not interpret any statement in this report as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. None of the authors has any affiliation or financial involvement that conflicts with the material presented in this report.

Publication date: 6/25/2025

___

References

1. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. Institute of Medicine. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. National Academies Press; 2000.

2. Newman-Toker DE, Nassery N, Schaffer AC, et al. Burden of serious harms from diagnostic error in the USA. BMJ Qual Saf. 2024;33(2):109-120.

3. World Health Organization. Diagnostic Errors. World Health Organization; 2016. Accessed May 28, 2025. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/252410

4. Balogh EP, Miller BT, Ball JR, eds. Committee on Diagnostic Error in Health Care, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine, The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. National Academies Press; 2015.

5. Newman-Toker DE, Schaffer AC, Yu-Moe CW, et al. Serious misdiagnosis-related harms in malpractice claims: The “Big Three” - vascular events, infections, and cancers. Diagnosis (Berl) 2019;6(3):227-240.

6. Core Elements of Hospital Diagnostic Excellence (DxEx). Patient Safety. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 17, 2024. Accessed May 28, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/patient-safety/hcp/hospital-dx-excellence/index.html

7. Fabre V, Davis A, Diekema DJ, et al. Principles of diagnostic stewardship: a practical guide from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Diagnostic Stewardship Task Force. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2023;44(2):178-185.

8. McDonald KM, Bryce CL, Graber ML. The patient is in: patient involvement strategies for diagnostic error mitigation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(suppl 2):ii33-ii39.

9. Schiff GD, Hasan O, Kim S, et al. Diagnostic error in medicine: analysis of 583 physician-reported errors. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(20):1881-1887.

10. Barwise A, Leppin A, Dong Y, et al. What contributes to diagnostic error or delay? a qualitative exploration across diverse acute care settings in the United States. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(4):239-248.

11. Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(13):1493-1499.

12. Gupta A, Snyder A, Kachalia A, et al. Malpractice claims related to diagnostic errors in the hospital. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;27(1):53-60.

13. Auerbach AD, Astik GJ, O’Leary KJ, et al. Prevalence and causes of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients under investigation for COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(8):1902-1910.

14. Gunderson CG, Bilan VP, Holleck JL, et al. Prevalence of harmful diagnostic errors in hospitalised adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(12):1008-1018.

15. Marshall HS, Milikowski C. Comparison of clinical diagnoses and autopsy findings: six-year retrospective study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141(9):1262-1266.

16. Cheraghi-Sohi S, Holland F, Singh H, et al. Incidence, origins and avoidable harm of missed opportunities in diagnosis: longitudinal patient record review in 21 English general practices. BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30(12):977-985.

17. Singh H, Meyer AND, Thomas EJ. The frequency of diagnostic errors in outpatient care: estimations from three large observational studies involving US adult populations. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(9):727-731.

18. Singh H, Giardina TD, Meyer AND, et al. Types and origins of diagnostic errors in primary care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):418-425.

19.Warrick C, Patel P, Hyer W, et al. Diagnostic error in children presenting with acute medical illness to a community hospital. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(5):538-546.

20. Schwartz A, Weiner SJ, Weaver F, et al. Uncharted territory: measuring costs of diagnostic errors outside the medical record. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(11):918-924.

21. Skinner TR, Scott IA, Martin JH. Diagnostic errors in older patients: a systematic review of incidence and potential causes in seven prevalent diseases. IntJ Gen Med. 2016;(9):137-146.

22. Hollnagel E, Wears RL, Braithwaite J. Resilient Health Care Net; 2015. Accessed May 28, 2025. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/issue/safety-i-safety-ii-white-paper

23. Hollnagel E. Is safety a subject for science? Saf Sci. 2014;67:21-24.

24. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Aviation Safety Reporting System Program Briefing. National Aeronautics and Space Administration; March 2024. Accessed May 28, 2025. https://asrs.arc.nasa.gov/docs/ASRS_ProgramBriefing.pdf

25. Ranasinghe U, Jefferies M, Davis P, et al.. Resilience engineering indicators and safety management: a systematic review. Saf Health Work. 2020;11(2):127-135.

26. Choi JJ. What is diagnostic safety? A review of safety science paradigms and rethinking paths to improving diagnosis. Diagnosis (Berl). 2024;11(4):369-373.

27. Holden RJ, Carayon P. SEIPS 101 and seven simple SEIPS tools. BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30(11):901-910.

28. SIDM Patient Engagement Committee. The Patient’s Toolkit for Diagnosis. Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine; October 2018. Accessed May 28, 2025. https://www.engagedpatients.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2022/11/…

29. Miller K, Ratwani R, Hose B-Z, et al. Documenting Diagnosis: Exploring the Impact of Electronic Health Records on Diagnostic Safety. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; August 2024. AHRQ Publication No. 24-0010-3-EF.

30. Patient and Family Advisory Councils Blueprint: A Start-Up Map and Strategy Guide. American Hospital Association; 2022. Accessed May 28, 2025. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2022/01/alliance-pfac-bluep…